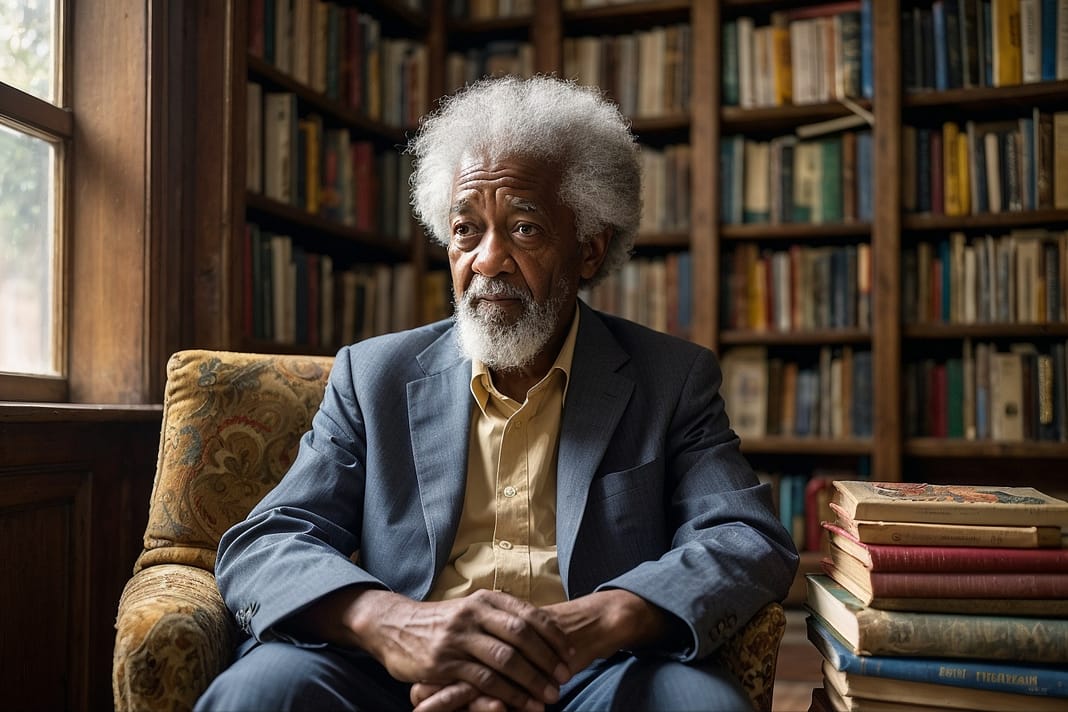

There are moments in history where the earth itself seems to tremble under the weight of a single voice. One of these voices belongs to Wole Soyinka, a man whose words rise from the soil of Nigeria, echoing across continents and generations. His is a voice that refuses silence, a spirit that has danced between prisons and stages, between the rituals of his Yoruba ancestors and the jarring modernity thrust upon his homeland. He is, simply, the kind of man whose story is inseparable from the story of a continent.

To speak of Soyinka is to speak of Africa’s song: a song interrupted, torn apart by colonialism, yet still humming, low and insistent, beneath the chaos of modernity. His work, like the thunder in Yoruba mythology, rumbles across time. Each line and every sentence are attempts to reclaim the rhythm of African life, to reassert the dignity of a people who had their voices stolen but never silenced. It is in this reclamation of voice that Soyinka finds his power—not just as a writer, but as an activist, a living testament to the idea that literature is more than words on a page. It is a call to action.

When Soyinka writes, he does not write for mere entertainment. His ink is infused with a sacred purpose, a belief that to tell a story is to perform a kind of spiritual labor. His plays—Death and the King’s Horseman, Kongi’s Harvest—are acts of defiance. They are Yoruba rituals in disguise, celebrations of African life, even when cast in the bleak shadow of colonialism. He evokes the gods, the ancestors, the unseen forces that tether the present to the past. And in doing so, he reminds us that Africa was never a blank slate for Europeans to scribble their stories upon. Africa was—and is—rich with its own stories, stories that cannot be erased by the stroke of a colonial pen.

But Soyinka’s defiance extends beyond the page. He is a man who has stood in the fire. The Nigerian Civil War tested his spirit, yet he remained unbroken. For 27 months, Soyinka was imprisoned in solitary confinement for daring to broker peace between the Nigerian government and the secessionist state of Biafra. In that isolation, with nothing but his thoughts and the suffocating silence of a prison cell, he transformed his suffering into a kind of intellectual resistance. The Man Died is not simply a memoir of his imprisonment; it is a manifesto. It declares that even in the face of brutality, the human spirit—when aligned with justice—cannot be crushed.

And still, the battle was not over. The 1990s would find Soyinka in exile, a political target of the brutal dictator, Sani Abacha. Yet, even in exile, his words had a way of finding their way home. They carried the weight of a continent’s suffering and hope. The global stage became his second home, and he wielded the pen like a spear, cutting through the complacency of the international community, calling attention to the rot within Africa’s leadership. The world was reminded that independence, for all its promise, was not enough. Soyinka saw, in the rise of African dictators, a tragic mirror of the colonial oppressors they had overthrown. Power, Soyinka warned, has a way of repeating itself—unless the people remain vigilant, unless the storytellers remain unafraid.

In his plays, we witness this struggle. Kongi’s Harvest presents us with a portrait of a tyrant, a man drunk on power, willing to sacrifice his own people in the name of progress. It is an allegory for post-colonial African leaders who, in Soyinka’s eyes, abandoned the moral compass that should have guided their leadership. They became what they despised, trading foreign rule for homegrown authoritarianism. The tragedy of African independence, Soyinka suggests, is that it gave birth to rulers who forgot what they were fighting for in the first place.

Yet, for all his critiques of African leadership, Soyinka is no mere cynic. His plays are also hopeful, imbued with a belief that tradition—if not manipulated for political gain—has the power to heal, to guide nations toward true liberation. Death and the King’s Horseman, for example, does not mourn the loss of a king’s horseman to colonial interference. It mourns the loss of understanding, the lack of respect for traditions that carry within them the wisdom of centuries. The clash between the British colonialists and the Yoruba people in that play is not simply about power; it is about the right to define reality, to define the terms of life and death. In Soyinka’s hands, this is not just an African struggle—it is a human one.

And it is here, perhaps, where Soyinka’s cultural implications stretch beyond the boundaries of Nigeria. His works are not simply African stories; they are global stories. In a world still struggling to define what it means to be modern, to be human, Soyinka offers a blueprint for a kind of hybridity that does not erase the past but carries it forward, even as it engages with the future. He is not nostalgic for a pre-colonial utopia; rather, he is fiercely committed to a world where African cultures are allowed to evolve on their own terms, without the heavy hand of foreign domination.

His literary activism has influenced a new generation of African writers who, like him, use the pen as a tool of resistance. From Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie to Teju Cole, Soyinka’s legacy can be felt in the way African writers today weave local traditions with global concerns. They, too, are navigating the complex waters of cultural hybridity, where the past and present meet, sometimes clashing, sometimes harmonizing, always negotiating.

But what does Soyinka’s work mean today? In an era where questions about identity, cultural appropriation, and the legacy of colonialism continue to dominate global conversations, Soyinka’s voice is more relevant than ever. His works remind us that identity is not a static thing, but a living, breathing force that must be nurtured, respected, and, above all, protected from the forces that seek to commodify or erase it. In a world where the fight for cultural survival is often played out on social media and in academic debates, Soyinka’s work stands as a reminder that this is not a new fight. It is the same fight he has been waging for decades, only now it takes on new forms.

So, when we ask ourselves today what role literature plays in shaping culture, we need only look to Wole Soyinka. He has shown us that literature is not a mirror that reflects the world as it is but a hammer that shapes the world as it could be. His works are not passive; they demand something of us. They ask us to see, to feel, and to act.

And in that demand, there is an invitation: to become part of a story that is still being written, a story where the future of Africa, the future of humanity, is one where tradition and modernity, the individual and the collective, justice and freedom can coexist. Soyinka has given us the words, but it is up to us to live them.

That is the gift—and the challenge—of Wole Soyinka’s legacy.

Discover more from The Reasoned Journey

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.