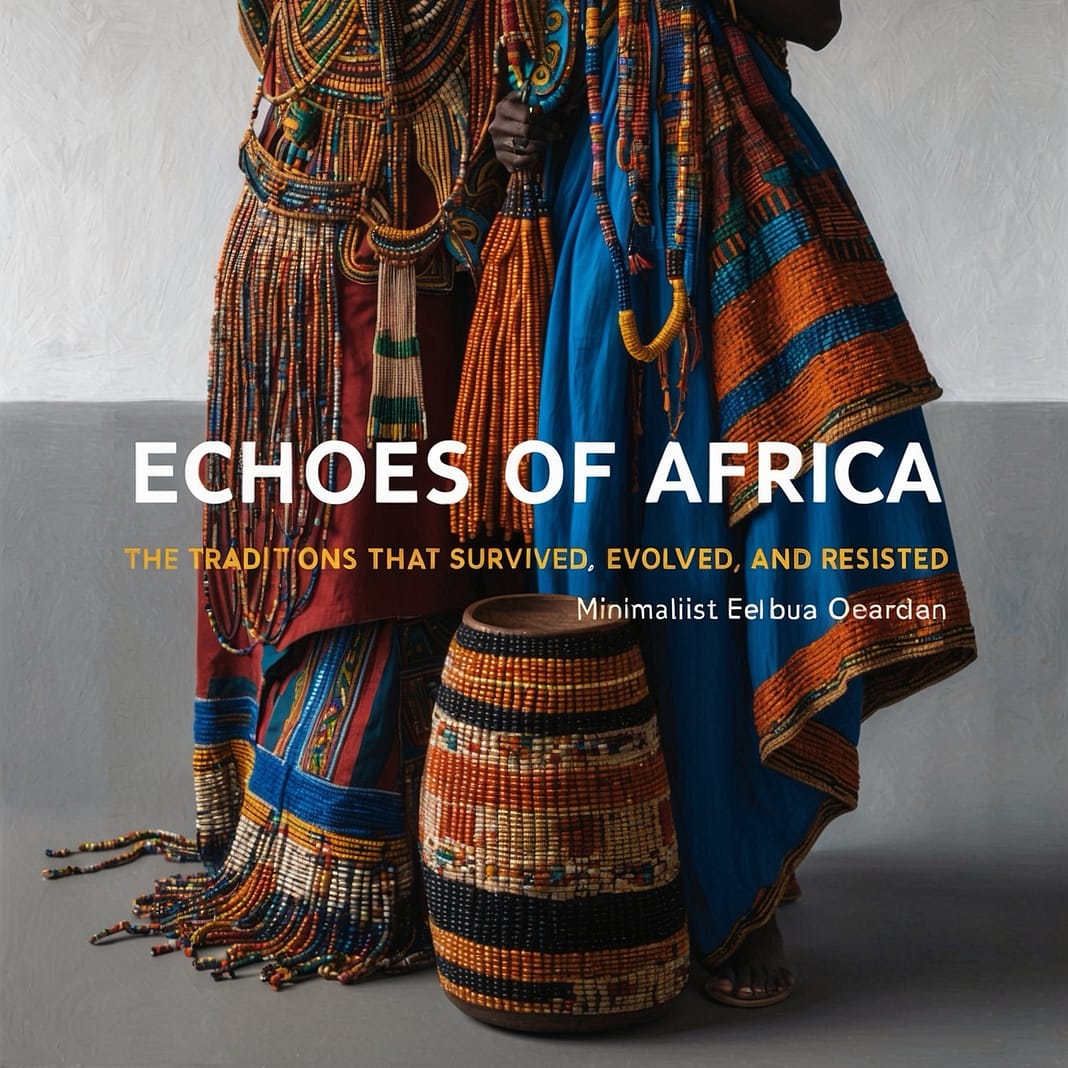

There’s an ache that lives in the traditions of the African diaspora, a weight that stretches across oceans, time, and unspeakable history. A diaspora is more than just movement—it’s the collision of bodies, stories, and spirits across centuries. And in the case of Africans displaced to distant shores, it’s the audacity to survive the unsurvivable, to hold fast to what you know in the face of the unknown, and to let memory become resistance.

What does it mean to carry traditions across those waters, to have the blood of ancestors whispering in your veins while the chains bite at your skin? How does one preserve a language, a song, or the rhythm of drums in a land designed to silence you? The answer lies in the tradition itself. It’s not just what you carry; it’s what you become.

Tradition as Survival, Tradition as Resistance

For those whose African heritage was ripped from the roots of the continent and planted in strange soil, tradition was never passive. It was active. It was the refusal to forget, the refusal to be forgotten.

When Africans were enslaved and brought to the Americas, Europe, and the Caribbean, they did not come as blank slates. They brought with them their languages, their gods, their songs, and their rituals. These traditions, once native to the soil of West Africa, Angola, the Congo, and beyond, were the lifeblood that tethered them to an identity threatened by erasure. And they would not go quietly.

The traditions of the Gullah people on the Sea Islands of South Carolina and Georgia are testaments to this resilience. Descendants of enslaved Africans who found themselves isolated on those coastal islands, the Gullah people wove together a culture so rich and so undeniably African that it thrived against all odds. Their language, a Creole that blends English with African elements, speaks of endurance. Their basket-weaving, rooted in West African craft, is a literal and metaphorical thread that ties them to their ancestors.

The very act of survival became an act of resistance. When you sing the songs of your ancestors in a language that the oppressor cannot understand, when you make the drum speak in rhythms older than the land you walk on, you are not just surviving—you are pushing back against the world that would see you disappear.

Spirituality as Defiance

Religion, too, became a battleground for the preservation of African identity. The spirits, gods, and ancestors that enslaved Africans worshipped didn’t vanish under the weight of colonial Christianity. Instead, they found new forms, new expressions. Haitian Vodou, Brazilian Candomblé, and Cuban Santería are not just religions; they are the fusion of African spiritual practices and the Catholicism forced upon them. But even in that fusion, the African essence persisted.

In Haiti, Vodou became the spiritual force behind the first successful slave rebellion in history—the Haitian Revolution. It was not enough to overthrow the chains that bound their bodies; enslaved Africans in Haiti called upon the lwa (spirits) to guide and protect them as they fought for freedom. Vodou wasn’t just worship—it was war. It was strategy. The ceremony at Bois Caïman, where revolutionaries invoked the spirits in a secret Vodou gathering, became a spark that set Haiti ablaze. A nation was born not just out of politics, but out of spiritual defiance.

In Brazil, enslaved Africans who practiced Candomblé found a way to honor their orishas (deities) under the watchful eyes of their Catholic oppressors by syncretizing their gods with Christian saints. But no amount of religious repression could fully extinguish the African fire in those rituals. The drumming, the dancing, the possession by orishas—all of it was deeply, undeniably African, even as it wore the mask of European religion. Tradition found a way to survive, to thrive, to rebel.

The Body as a Vessel for Memory

Music and dance became the most visceral forms of preserving African tradition, especially when the body itself became the only thing that couldn’t be taken. Even as languages were lost or forcibly erased, rhythm remained. Across the diaspora, the music and dance of African-descended people carried echoes of the motherland. It’s there in the ring shout of the Gullah, the capoeira of Brazil, the spirituals of enslaved Africans in the United States, and the drumbeats that pulse through Trinidad’s Carnival.

Carnival, that riotous celebration of life, freedom, and defiance, is itself a tradition born out of the merging of African and European cultures. But don’t be fooled by the masks and glitter; Carnival’s roots are in resistance. The African masquerade traditions brought to the Caribbean by enslaved people allowed them to mock their colonial oppressors, to reclaim public space, and to celebrate their survival. Today, Carnival is a global phenomenon, but its heartbeat still resonates with the rhythm of African drums, the resilience of African spirits.

The Weight of Tradition in the Present

In the current moment, as conversations about the African diaspora trend across the globe, one of the central questions remains: Why are these traditions still important? The answer lies not only in the past but in the present. The traditions of the African diaspora remind us that even when systems conspire to erase a people’s history, that history finds ways to live on. They are living, breathing testaments to the fact that no amount of displacement, oppression, or time can fully sever the ties that bind us to our ancestors.

Today, as the descendants of the diaspora confront systemic racism, police brutality, and the ongoing struggle for civil rights, these traditions serve as a wellspring of strength. The spirituals that once carried messages of escape from the plantations now inspire movements for justice. The rhythm of the drum, once a signal for rebellion, now beats at the heart of protest marches.

Tradition, in the context of the African diaspora, is not static. It evolves, adapts, and responds to the moment. But it never loses its core. It never forgets. It’s a bridge between the past and the present, between the ancestors and the descendants. In the rituals, the songs, and the dances, there is a deep knowing—a remembering that defies time and space.

The Soul of the Diaspora

To speak of the traditions of the African diaspora is to speak of memory. It’s to recognize that the body remembers what the mind might forget, that the spirit holds on to what history tries to bury. It’s to honor the fact that the African traditions carried across oceans, against all odds, have not only survived but thrived. They have become the lifeblood of communities across the globe, giving shape and meaning to a people’s journey through pain, struggle, and, ultimately, triumph.

These traditions are not just relics of a lost world—they are living, breathing parts of the diaspora’s soul. They are reminders that, even in displacement, there is a home. Even in exile, there is belonging. Even in silence, there is a song waiting to be sung.

In a world where identities are still contested and histories still debated, the traditions of the African diaspora stand as a testament to the resilience of a people who refused to be erased. And as long as the drum beats, as long as the spirit dances, these traditions will carry us forward, one generation to the next, unbroken.

Discover more from The Reasoned Journey

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.