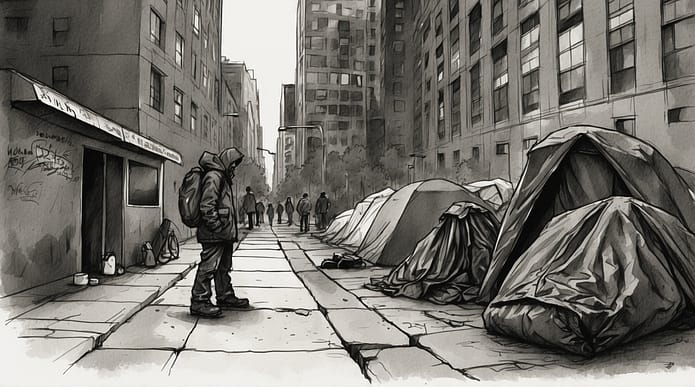

There is a bitter irony that we, as a society, have mastered the art of feeding those behind bars while leaving our brothers and sisters on the streets to hunger and wither. It is a silence we walk past, a discomfort we turn away from, and yet it lingers—whispers of our shared failure. How is it that a man who has taken life, who has fractured the sacred bonds of community, can rely on three meals a day, while a woman with no home, no safety, no shelter, finds herself abandoned? It is the kind of question that makes us choke on our own morality, forcing us to confront the widening gulf between the promises we make and the justice we fail to deliver.

This is not just about logistics or laws. This is about the soul of a society, about the stories we tell ourselves to ease the discomfort of our privilege. It’s about whom we deem worthy of the most basic human dignity.

Hunger in the Shadows. Whom Do We Care For?

Let us pause and consider the machinery of the state. Inside the cold walls of a prison, there is an efficiency—cold, clinical, but effective. We ensure the incarcerated are fed. After all, it is mandated by law. The state takes care of those it has removed from the streets, feeding their bodies even if their spirits are left to rot in the confines of their guilt. But where is the law for the homeless? Where is the mandate that says they, too, deserve to eat, to live with a roof over their heads? It is in the absence of such laws that our hypocrisy is laid bare.

For many, the homeless remain invisible. Their hunger is silent, tucked beneath the weight of society’s shame. “Why don’t they just get a job?” “What brought them to this point?” we ask. But these questions are deflections, echoes of a system that chooses to look away rather than confront the ugly truth—that homelessness is not about individual failure, but collective abandonment.

James Baldwin once wrote, “Anyone who has ever struggled with poverty knows how extremely expensive it is to be poor.” The homeless pay a price that the privileged cannot fathom. And still, we refuse them what even the convicted are guaranteed: nourishment, a place to rest, the basic respect owed to every living soul.

The Moral Paradox of Priorities

We should not need to remind ourselves that hunger is a universal human condition, unmoored from the labels we place on people. Yet, here we are—facing a reality where prisoners are fed not because of compassion, but because it is the law. It is what keeps the system running smoothly. The homeless, on the other hand, have no such system in place. Their nourishment, if it comes at all, is left to the unpredictable winds of charity.

There are those who would say that prisoners are the responsibility of the state, while the homeless are not. But we must ask ourselves—why? What does it say about us that we have built a system that prioritizes punishment over prevention, incarceration over care?

In this cruel contradiction, we reveal our collective priorities. We would rather sustain those we have condemned than uplift those we have forsaken. Is this justice? Is this mercy?

A Reflection on Power and Perception

We have constructed prisons not only of steel and concrete but of thought and perception. We have made it easier to feed criminals because, in doing so, we believe we are maintaining order. Meanwhile, the homeless—those whose stories are often shaped by systemic failures—are dismissed, their plight seen as an inevitable, if tragic, part of the human condition.

We must grapple with this reality: The criminal is visible, the homeless are not. The criminal is accounted for, the homeless are forgotten. We see this dichotomy in our policies, our practices, and even in our hearts.

What would it mean to shift our gaze? To see the homeless as deserving of care, of food, of shelter, as much as anyone who finds themselves in prison? To realize that hunger is not just the absence of food but the absence of care, the absence of belonging?

Trending Questions, Deeper Reflections

In recent times, the conversation around homelessness has gained traction, especially as housing prices rise, wages stagnate, and more people find themselves on the brink of poverty. Politicians and activists debate solutions—universal basic income, affordable housing, mental health services—but behind these policy discussions, there lies a deeper question: Do we, as a society, believe that the homeless are worthy of the same dignity we afford to even the worst among us?

The question of homelessness intersects with issues of race, class, and mental health. It forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about who bears the brunt of societal neglect. The homeless are not a monolith; they are individuals, each with a story that is often shaped by the failings of the very systems that now refuse to care for them. And yet, we persist in asking the wrong questions—How can we punish those who break the law?—while neglecting the more urgent one: How can we care for those who have been broken by the law?

Toward a More Just Society

To feed the prisoner but not the homeless is to accept a world where punishment is valued more than compassion, where the incarcerated are sustained but the marginalized are cast aside. And this must change. It is not enough to feed the body of a criminal while starving the soul of society.

We must reimagine what it means to care for one another. We must recognize that feeding the homeless is not just an act of charity but an act of justice. For until we can feed the hungry—all of the hungry—without exception, we will never be able to claim that we are a truly just society.

This is not a call to abandon those in prison but rather a plea to extend the same care we show them to those who wander the streets, who sleep under bridges, who line up at soup kitchens hoping for a meal. It is to say that, in a world as rich as ours, no one should go hungry. Not the prisoner. Not the homeless. Not anyone.

It is, ultimately, a call to remember our shared humanity, to tear down the walls we have built between us, and to feed those who hunger—not just with food, but with the dignity that every person deserves.

In the words of Baldwin, “For these are all our children, we will all profit by or pay for what they become.” What will it cost us to keep looking away? What will we gain if we finally see?

Discover more from The Reasoned Journey

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.